Understanding Energy Storage Systems and Technologies

Outline:

– Why energy storage matters now

– Electrochemical storage: lithium-ion, sodium-ion, and flow batteries

– Mechanical storage: pumped hydro, compressed air, and flywheels

– Thermal and chemical pathways: heat, hydrogen, and hybrid systems

– From options to outcomes: selecting, sizing, and deploying storage

The Role and Value of Energy Storage Today

Energy storage turns fluctuating supply and flexible demand into a well-rehearsed duet. Think of it as a time machine for electrons: charging when energy is abundant and inexpensive, then delivering it when demand peaks or the wind calms. As solar and wind shares grow, many grids experience midday oversupply and evening ramps. Storage absorbs the midday spill, easing curtailment and smoothing operations. In regions with high solar penetration, curtailment can reach double-digit percentages during shoulder seasons; shifting even a fraction of that surplus to later hours can lower system costs, reduce emissions, and improve asset utilization. Beyond renewable integration, storage strengthens resilience, providing fast frequency response in milliseconds, black-start capability after outages, and backup power for critical loads during storms or wildfires.

Storage value flows through diverse services. On short timescales, devices handle frequency regulation, voltage support, and transient stability. On multi-hour horizons, they perform peak shaving, energy arbitrage, and capacity adequacy. For longer horizons—days to seasons—storage can carry energy across weather patterns or even between summer and winter. The practical outcome is a more flexible grid that can accommodate electrified heating, industrial loads, and growing vehicle charging without building out generation and wires at the same pace as peak demand. This flexibility also helps defer certain grid upgrades, giving planners more options and time.

Where does storage fit for different stakeholders? Commercial facilities use it to trim demand charges and keep production lines running during brief outages. Communities deploy neighborhood-scale systems to island during emergencies. Utilities employ large installations to stabilize corridors constrained by transmission limits. Policymakers see it as a tool that can be technology-neutral, procured competitively, and compensated for measurable services. Some common use cases include:

– Time-shifting surplus photovoltaic generation into the evening

– Frequency and voltage support to steady grid operations

– Backup and black-start capability during grid restoration

– Capacity contributions during heatwaves and cold snaps

Ultimately, storage is not a single technology but a toolbox. Picking the right tool requires understanding performance metrics—round-trip efficiency, cycle life, response time, energy-to-power ratio, footprint, and safety—alongside the revenue streams or cost savings it can capture.

Electrochemical Storage: Lithium-Ion, Sodium-Ion, and Flow Batteries

Electrochemical systems dominate new deployments because they respond quickly, scale modularly, and integrate readily with power electronics. Lithium-ion batteries are the most widely installed today, offering high round-trip efficiency (often 90–97%), fast ramping, and compact footprints. Their energy density at the cell level commonly ranges from roughly 150 to 300 Wh/kg, which is helpful where space is tight. Project costs vary with duration, interconnection, and balance-of-plant, but many grid-tied installations land in a broad range from the low hundreds to several hundred USD per kWh installed. Cycle life depends on chemistry, operating window, and duty cycle; thousands of cycles are typical, and careful thermal management plus conservative state-of-charge ranges can extend longevity.

Sodium-ion batteries are drawing attention as a complementary option that relies on widely available materials. Although energy density is lower on average than many lithium chemistries, early grid applications show promise for stationary use where volume and weight are less constrained. Round-trip efficiency can reach about 80–90%, with performance less sensitive to cooler temperatures than some lithium variants. For developers, sodium-ion may provide supply chain diversification and potential cost stability over time, especially for multi-hour stationary systems.

Flow batteries, including vanadium-based and zinc-halide variants, store energy in liquid electrolytes held in external tanks. Their power (the stack) and energy (the tanks) are decoupled, which allows relatively straightforward scaling to 6, 8, or even 12 hours without redesigning the stack. Round-trip efficiency typically ranges from about 65–85%, and cycle life can be high—often measured in tens of thousands of cycles—because the electrochemical reactions can be more benign with respect to electrode degradation. Flow systems generally require more floor area and have lower energy density, but they offer compelling durability for high-throughput daily cycling. Lead-acid, a stalwart of backup power, still finds a role where very low upfront cost and simplicity matter, though its efficiency and cycle life (roughly 70–85% and hundreds to a few thousand cycles) make it more suitable for standby rather than heavy cycling.

How to choose among these? Consider:

– Required duration: sub-hour regulation versus 2–8 hour peak shifting

– Throughput: daily cycling favors chemistries with slower degradation

– Site constraints: footprint, noise, and permitting

– Safety: thermal management, gas venting, and fire suppression

– Economics: capital cost, efficiency losses, warranties on energy throughput

No single electrochemical family wins every scenario. Lithium-ion excels at fast response and compact installations. Sodium-ion can help contain material costs for stationary needs. Flow batteries shine where long duration and heavy cycling are central. A portfolio approach—matching chemistry to duty—often delivers the strongest results.

Mechanical Storage: Pumped Hydro, Compressed Air, and Flywheels

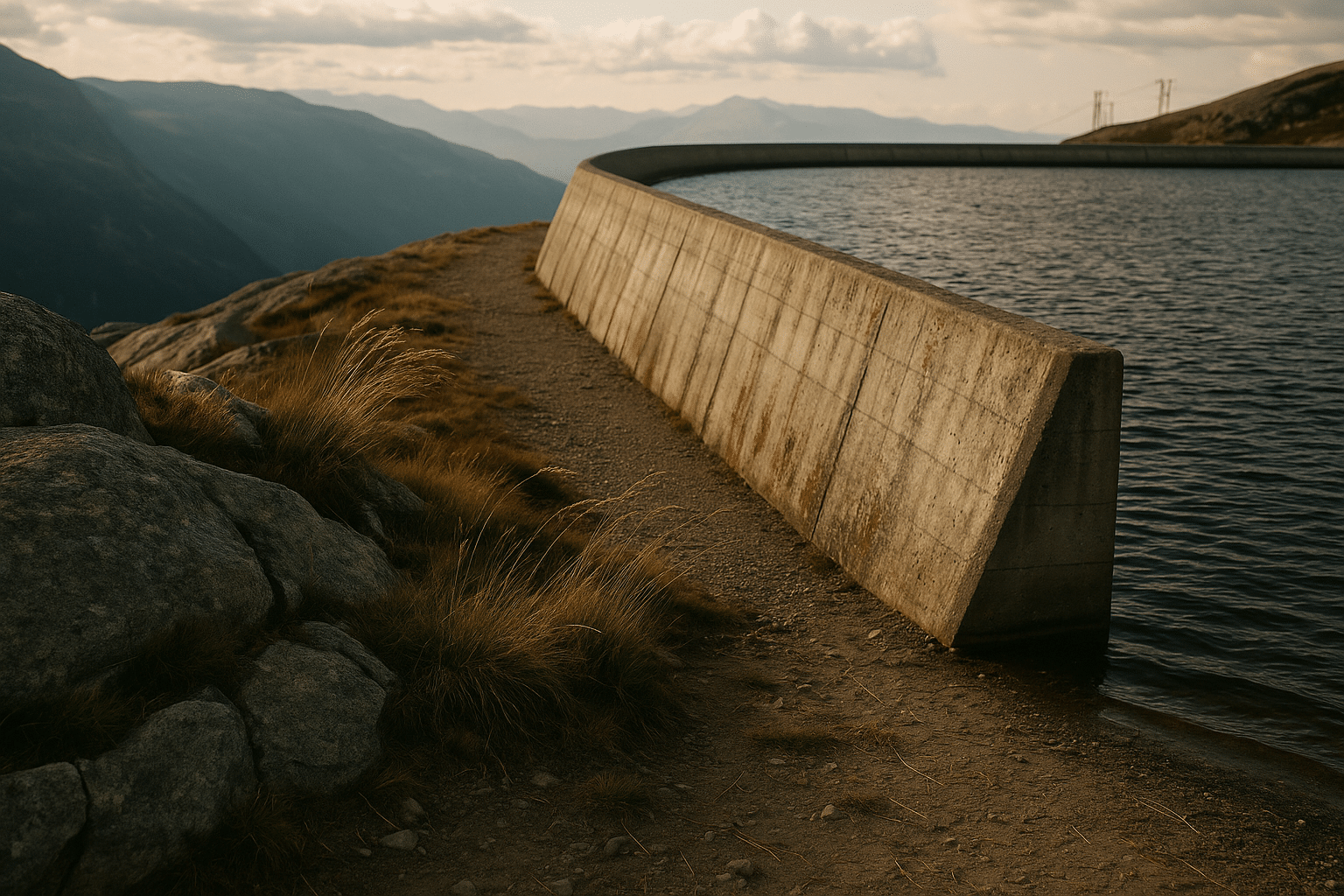

Mechanical storage harnesses gravity, pressure, and rotational inertia to move large amounts of energy with robust, long-lived assets. Pumped hydro storage, which moves water between reservoirs at different elevations, accounts for the majority of existing grid storage worldwide. When electricity is plentiful, water is pumped uphill; when needed, it flows down through turbines to generate power. Round-trip efficiency typically falls between 70–85%, and plants can operate for decades with proper maintenance. Duration can be extensive—6 to 20 hours is common, and some sites can go longer—making pumped hydro suitable for daily cycling and even multi-day events if reservoirs are large enough. The trade-offs are site-specific: suitable topography, water availability, and environmental considerations drive feasibility and timelines.

Compressed air energy storage (CAES) uses off-peak electricity to compress air into underground caverns or engineered vessels, then expands that air through a turbine to produce power. Traditional diabatic CAES relies on burning fuel during expansion, yielding lower round-trip efficiencies (often in the 40–55% range). Advanced or adiabatic approaches aim to capture and reuse compression heat, lifting efficiency into the 60–70% range while reducing or eliminating combustion. CAES offers very large storage capacities with durations that can exceed 10–24 hours. However, it requires appropriate geology, careful thermal management, and attention to system integration with the grid and any co-located renewables.

Flywheels store energy kinetically in a rapidly spinning rotor kept in a low-friction environment. They are agile specialists: response in milliseconds, high cycle counts (hundreds of thousands), and round-trip efficiency commonly between 85–95%. Energy capacity per unit is comparatively low, so they are used for seconds-to-minutes services such as frequency regulation, voltage support, and uninterruptible power for sensitive equipment. Modern flywheels typically feature composite rotors in vacuum housings with magnetic bearings, paired with robust power electronics and protection systems. Their durability and minimal performance degradation over frequent cycling make them well-regarded for ancillary services where precision and speed matter.

When comparing mechanical options, key questions include:

– Geography: elevation differences for pumped hydro; caverns for CAES

– Duration needs: minutes (flywheels) versus many hours (pumped hydro, CAES)

– Environmental footprint: water use, land use, and habitat impacts

– Project life and O&M: long-lived civil works versus rotating machinery upkeep

– Grid interface: ramp rates, inertia contributions, and black-start utility

Mechanical storage complements electrochemical systems by covering long durations with potentially lower lifetime costs in the right settings, while delivering inertia and grid-stabilizing characteristics that power electronics alone do not natively provide.

Thermal and Chemical Storage: Heat, Cold, Hydrogen, and Hybrids

Thermal storage shifts energy by holding heat or cold in materials that can later warm buildings, drive industrial processes, or generate electricity. Hot water tanks integrated with district energy systems are straightforward and cost-effective, particularly for space heating or domestic hot water. Molten salt tanks paired with solar thermal plants can hold many hours of heat, typically delivering 6–12 hours of dispatchable power via steam cycles. Round-trip efficiency depends on the pathway: storing heat for heat can exceed 90% at the point of use; converting stored heat back to electricity is generally lower due to thermodynamic limits. Phase-change materials add compactness by storing latent heat at specific transition temperatures, useful for building load shifting or process temperature control.

Cold storage targets cooling loads—a major driver of peak demand in warm climates. Ice or chilled-water systems make cooling at night when electricity is cheaper and ambient temperatures are lower, then discharge during the day. This approach can shave peaks at commercial campuses, reduce chiller sizing, and allow operators to participate in demand response programs. In food logistics and data centers, thermal buffers can maintain temperature during short outages, improving resilience without relying solely on generators.

Chemical pathways store energy in molecular bonds. Power-to-gas converts electricity to hydrogen through electrolysis. That hydrogen can be used on-site, stored in tanks or underground formations, or converted into derivatives such as ammonia or synthetic methane. Round-trip efficiency for electricity-to-hydrogen-to-electricity often falls in the 25–45% range today, reflecting conversion losses in both electrolysis and reconversion via fuel cells or turbines. Despite lower efficiency, hydrogen excels at long-duration and seasonal roles because it’s easier to store large quantities of energy chemically than electrochemically. For industries that need high-temperature heat or feedstocks, hydrogen and its derivatives can decarbonize processes that batteries cannot directly serve.

Hybridizing thermal and chemical storage with renewables can unlock additional value:

– Using midday solar to make hydrogen, then blending it into gas systems within allowed limits

– Pairing heat pumps with thermal tanks to absorb wind power overnight and serve morning heating peaks

– Marrying long-duration hydrogen with short-duration batteries to cover both daily and multi-day needs

– Integrating waste heat recovery with district thermal networks for local flexibility

Considerations include siting (tanks, compressors, safety zones), end uses (heat versus electricity), and market structures that reward capacity, flexibility, and clean fuels. In practice, thermal and chemical storage complement batteries and mechanical options, extending the time horizons over which clean energy can be banked and used.

From Options to Outcomes: Selecting, Sizing, and Safely Deploying Storage

Turning ideas into projects starts with anchoring technology choices to specific services, timelines, and constraints. A useful way to shortlist options is to map applications to duration and cycling intensity. Fast-response services like frequency regulation and ride-through typically point to lithium-ion or flywheels. Multi-hour peak shaving and solar shifting invite lithium-ion, sodium-ion, or flow batteries, while very long durations can be the domain of pumped hydro, CAES, or hydrogen-based systems. Behind the meter, space, noise limits, ventilation, and proximity to loads shape design. Front-of-the-meter plants must navigate interconnection queues, deliver grid services under clear performance metrics, and align with transmission constraints.

Key metrics guide comparisons:

– Round-trip efficiency: how much energy is returned after storage

– Cycle life and calendar life: expected throughput and years of service

– Energy-to-power ratio: duration flexibility at reasonable cost

– Response time and ramp rate: suitability for ancillary services

– LCOS: levelized cost of storage across capital, O&M, losses, and degradation

– Safety and compliance: gas detection, fire barriers, remote monitoring, and emergency response planning

These metrics interplay with project economics. For example, higher efficiency helps in energy arbitrage markets with tight spreads, while long cycle life matters most for daily-cycling applications. Capacity payments and ancillary service revenues can stabilize cash flows for assets providing reliability benefits beyond pure energy shifting.

Practical steps improve outcomes. Start with a technology-agnostic specification that defines required services, duty cycles, and performance tests. Seek warranties linked to energy throughput and availability, not just years. Right-size duration to the revenue stack: 1–2 hours for fast services, 2–6 hours for peak support, and longer only when markets or reliability needs justify it. Consider modularity to add capacity as prices evolve. Address safety early—site separation, ventilation paths, detection systems, and training for local responders reduce risk and speed permitting. Plan for end-of-life with pathways for reuse or recycling, and incorporate monitoring analytics to optimize dispatch while safeguarding health of the asset.

For leaders weighing investments—utilities, campuses, and community energy groups—the payoff is a portfolio that can flex with the future. Combining complementary technologies hedges risk: batteries for fast, frequent duties; mechanical or thermal assets for long, steady roles; hydrogen for seasonal gaps or industrial heat. Clear procurement, transparent performance data, and thoughtful siting turn storage from a buzzword into dependable infrastructure. In short, choose the tool that fits the job, verify it with data, and design for safe, durable service so storage delivers reliable value for years to come.